This is part 4 in a 6-part correspondence series between me, Henriette Lazaridis, and writer Meta Wagner. Meta is writing three letters at Page Fright and I’m writing three here at The Entropy Hotel, and we’ll cross-post them.

Links will be added as the letters get published: letter 1, letter 2, letter 3, letter 4, letter 5, and letter 6.

Meta, you wrote about useful fears—and fears that we really do best to overcome and set aside. I do think it’s important to examine this notion that it’s valiant to overcome fears. Even the very phrasing of that loads the whole issue with moral value. Overcoming is a good thing. Those who overcome are heroic, noble. So if fears are a thing to overcome, that suggests that holding onto a fear is somehow weak and ignoble. We need, I think, to formulate the whole concept differently. “Holding on” suggests neediness and weakness, and we need a better phrase. Maybe it’s a question of something more neutral. Carrying our fears along? Does that sound like we might even be taking them along like a friendly pet on a leash? Honoring our fears? Does that sound too foofy? Maybe. But you get the idea. It’s ok to be afraid—in certain situations, about certain things.

Consider, for instance, the situation in which an athlete—a hiker, let’s say—is faced with an exposed ridgeline (like the summit of Katahdin in Maine, which I’ve not yet been to but which is legendary). Consider that this hiker might be nervous about putting a foot wrong and falling really badly. Is it always always always the right thing for that hiker to keep going, to overcome their fear? Maybe not. Maybe that hiker is so afraid that they will tremble so much that they will put a foot wrong and will tumble who knows how far and become seriously injured. Maybe it’s ok for that hiker to say, hey, you know what, this is not my thing today. That’s not weak or needy. It’s wise.

I do believe there are fears even in the creative (non-mountain-ridgeline) world that should be heeded. Most of us writers thankfully don’t face actual peril as the cost for expressing our ideas. But some do—whether it’s the memoirist whose family can cause them serious emotional or even physical harm in payment for words perceived as attacking, or the political writer whose ideas might land them in prison. We can’t simply say, blithely, of course you must overcome those fears and write! Maybe yes, but it should be ok for a writer to acknowledge (or honor, or carry along) the fears that are telling them to preserve their personal safety.

On another note, I’ve been thinking of the times when we can become afraid of good things. For instance, consider the writer who has a great couple of days of dedication (not talking about output here but dedication to the task), and who really enjoys those writing sessions (not for their quantity, necessarily, but for the experience). You’d think that the inevitable next thing would be that the writer would continue to do this. It was great, so I’ll go back to it and have this good experience over and over and over. And yet, we often don’t. Why is that?

Why can’t we seem to sustain a good writing/creative process even in the face of no new conflicts or scheduling distractions?

I have a feeling it’s because we become afraid that this is just too good to last. We fear that the goodness will run out. That we maybe even imagined the goodness and by, say, Wednesday, we’re exaggerating how good the writing experience was on Monday, so surely it’s ok if we skip it altogether that day. Now, maybe this is my Greek evil-eye awareness (see Letter One!) that tells me good things don’t last. (That and a lifetime of Joni Mitchell songs with lyrics like “nothing lasts for long” and other cheery sentiments.) Or maybe it’s a kind of self-preservation.

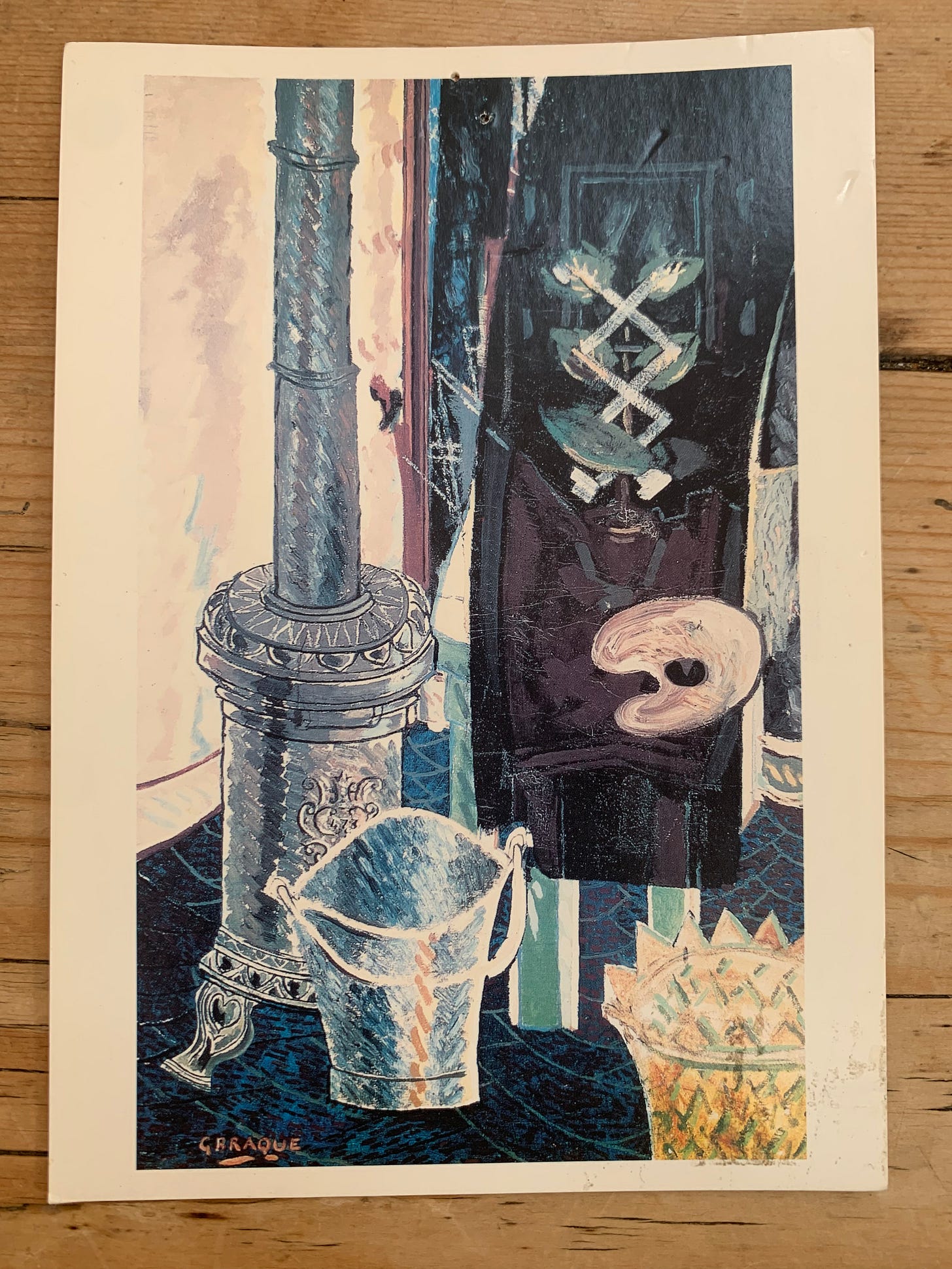

Many years ago, while visiting a good friend in London, we went to the Royal Academy of Art to see a Braque exhibit. We strolled and gazed and chatted. And then I saw this one painting—of Braque’s studio and woodstove—and stopped dead in my tracks. I swear to you that the painting was somehow vibrating, that the yellow and the heavy outlining was vibrating in the way that a Rothko vibrates (though with a completely different look). I couldn’t tear myself away. Gillian came and looked at it with me, but it didn’t do the same thing for her. She waited patiently until I had decided I could tear myself away because it was, finally, time to leave.

I know where that painting is, when it’s not on loan to the Royal Academy. It’s in the British art collection at Yale. It’s a three-hour drive away from me. I have often thought of making the drive (after ensuring that it’s not stored away but is actually on display). But have I ever? Nope. Because I’m afraid. I’m afraid that the painting won’t vibrate like that for me again. And then instead of remembering that experience as if it was yesterday, I’ll remember the repeat viewing and the (possible) disappointment.

The possible disappointment. That’s the key part. Because, sure, there’s a chance that I might go and see the Braque and it will once again stun me with it’s strange power. Joni Mitchell could be right, after all. So I don’t want to risk it. Risk and fear are sides of the same coin, I think. And it’s a coin-toss (ha!) whether the risks we take will have positive or negative outcomes. Most of the time, our fears can be set aside because we can have a reasonable expectation that the outcome of our actions will be positive. Sometimes, either the negative is so alarming/worrying or the risk calculation so certain that we should listen to the voice that says don’t.

I came across a review the other day of a book about financial risk (because why not), and the author used the phrase “owning your risk”. He was discussing the history of workers being considered liable (or not) for injuries incurred on the job. And he introduced (to me, anyway) this concept of owning risk. We do own our risk, as individuals living our lives. That’s both a blessing and a curse. We are responsible for our actions, and yet we have only our own consciences to guide us in what actions are “safe” to take. Would I hike the knife edge on Katahdin? Maybe. Did I put myself in position to hike a similarly exposed ridge in the Alps? Nope. Would I write something experimental, or provocative, or controversial? I think yes.

What about you? What fears would you listen to? What fears would you set aside? What risks would you take?

[And one more thing: in the annals of not being afraid, I am joining with writer friend Anjali Mitter Duva to start a new publishing company. It will help us a lot in our preparation and research if you would fill out this quick survey of reader habits!]

Henriette, I really enjoyed reading your response. And I especially liked your story about how we fear that something we loved won't strike us as powerfully if we return to it again, as in the case of the Braque painting. I feel that way about books that I read as a pre-teen, when reading became a passion: Gone with the Wind, Exodus, Rebecca, and so many more. I've resisted the urge to re-read some for this very reason. But, as you've pointed out, this is a fear that doesn't need to be overcome. I think I'd rather hold onto my memory of the "first time" when it comes to certain books. With fears that are standing in the way of us enjoying life, achieving our writing goals, etc., some of those are more important to address.

Thank you for these reflections. Eleanor Roosevelt said, "do one thing every day that scares you." It is a path to fearlessness and, thus, to knowledge.