Last month I wrote about a recent complicated hiking/climbing trip to Chamonix. I wrote about managing expectations and how I had wrestled with the disappointment borne not really out of not summiting anything (let alone Mont Blanc itself) but out of a feeling that a story was being written for me that didn’t quite fit. In fact, that’s not at all how I put it in last month’s piece, but this is what I want to talk about now:

about how there is so much more to a physical adventure than the physical dimensions of it. Adventures have much to do with the stories we tell about them—the stories we tell ourselves, the stories about ourselves we tell to others.

In our Chamonix experience, we were a climbing group of six. (And let me pay a small homage to our little group—two married couples, and two friends, who had a lovely camaraderie.) We spoke together often about our shifting reactions to our own individual abilities as well as to whatever challenges the mountains were offering up to us. At one point, we came together with one story, and one of us relayed it to our guides: to tell them we did not feel ready to attempt Mont Blanc.

Almost two months later, it occurs to me that our public story might have held six private tales within it. No matter that we all appeared to agree on the conditions, on our preparedness, on any of the rest of it, we surely each came away with a different narrative of the trip. If were were to stand above it all somehow and see all the stories together, we would probably have some sort of mountaineering Rashomon.

Not every adventure ends with all its participants able to narrate its story. Mountaineering is full of competing stories or outright mysteries about the tragic fates of so many. Think of George Mallory, for one, and the question of whether he was on his way down from Everest’s summit or up. Even in expeditions where it’s possible to leave records behind, how do we know the explorers are telling the truth? Consider Robert Peary, who may well have faked his data of reaching the North Pole (and whose medal from the Royal Geographical Society was given only “for Arctic Exploration”—and designed by the sculptor Kathleen Scott, who just happened to be married to Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott).

And think of Robert Scott, who documented his 1911 Antarctic expedition in detailed diaries and journals. Scott raced Roald Amundsen to be first to the South Pole, was defeated by the Norwegian, and died along with his four companions on the way home. His amazing line—written literally as he was dying of starvation and hypothermia and severe frostbite: “Had we lived, we would have had a tale to tell”. That has to be one of the most impressive bits of adventure prose.

For my whole life, I’ve been borrowing a famous line attributed to Titus Oates. He left Scott’s Polar Party tent during a blizzard, already in near-death condition, and said “I am just going outside and may be some time.” But we only know that Oates said this because Scott quoted him in his diaries. Scott had a gift for prose, and so the fact remains: when you’re the only one writing some things down and nobody offers a counter or a confirmation, your word stands, whether it’s true or not. All these years I’ve been wryly quoting Oates when I go out to run errands, but perhaps it isn’t Oates I’ve been quoting, but Scott.

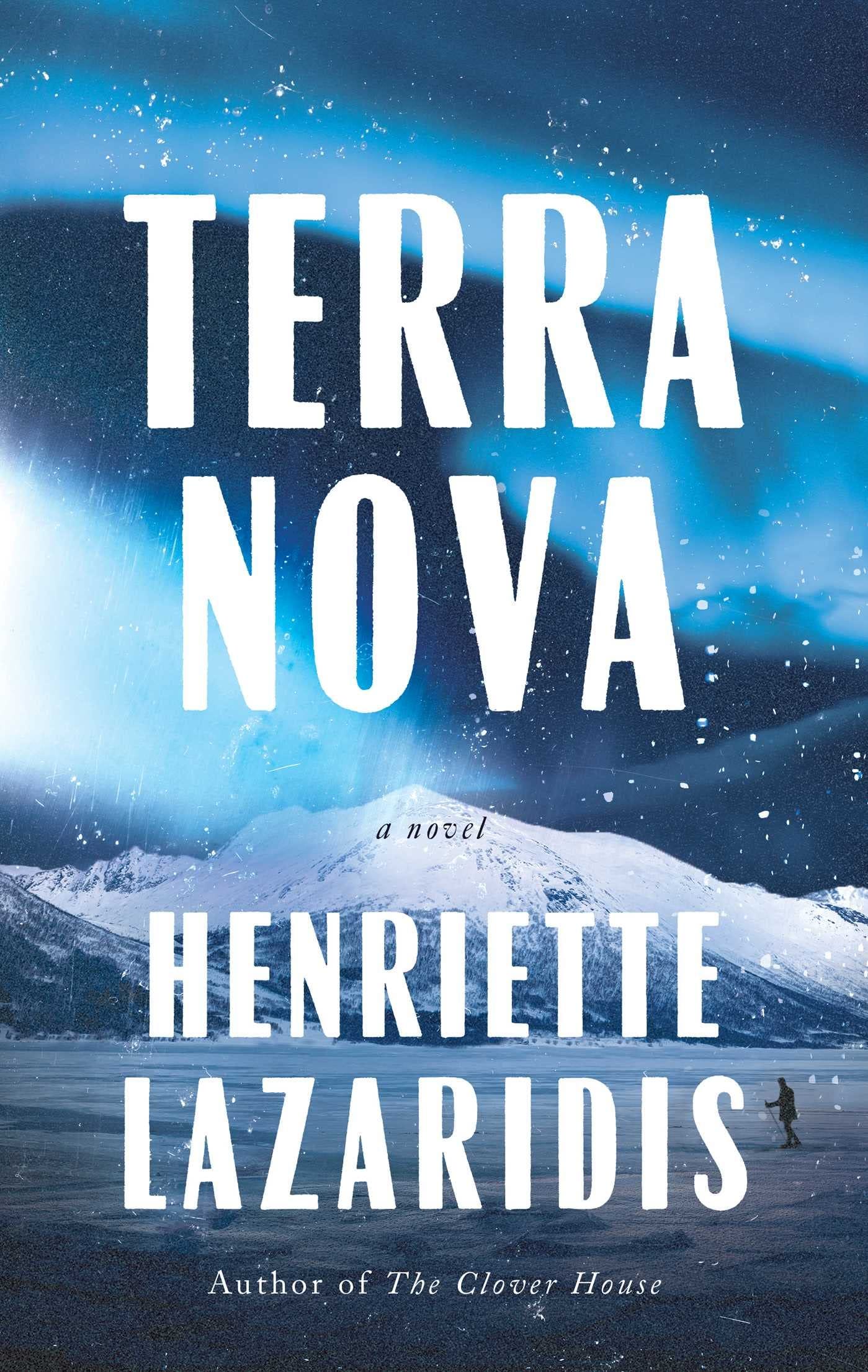

One month from now, my new novel Terra Nova will come out from Pegasus Books.1 The book is inspired by Robert Scott—specifically by the thought of what it must have been like to arrive at the South Pole and find your rival’s flag planted there, announcing that you’ve lost. Think about it: No one else is around, it’s just ice and snow and you and your four companions, and the Norwegian flag. What story would you tell? What story would you arrange to be able to tell? Terra Nova will, I hope, put these questions into dramatic play, along with questions about who gets to tell the truth, and—kind of—how many different kinds of truth there are.

After our trip to Chamonix, our group of six climbers dispersed to various parts of the United States, each one to tell the story of what happened in the mountains2. Maybe I show up in another story in a way I wouldn’t recognize. Maybe the others wouldn’t recognize themselves in my story. What’s certain is that our every telling stakes a new claim, for ourselves, on what we felt was our true experience, whether it was true or not.

Yes, please, order tons, and after it’s come out, buy lots more!

Not trying to be cryptic about some event of huge magnitude. Just making the point that even small-scale events will have their varied and various stories.

Henriette, this piece sparked a lot of thoughts about storytelling and the subjective nature of truth (not to be confused with the purposeful distortion of the truth out there these days). But, I've gotta admit my favorite part was that you use the Oates (or Scott) quote when you're simply running out to do errands! Can't wait for Terra Nova!