I spent all of February in Antarctica.

Strictly speaking, though, I wasn’t in Antarctica because I was on a ship. And while we landed in a number of places along the way, our journey of 7,464 miles followed the outer edge of that continent, beginning at the southern end of New Zealand and ending in Argentina’s Tierra del Fuego. So, I wasn’t so much in Antarctica as I was at Antarctica. I was, most of all, overwhelmed by Antarctica.

Since I was a little girl, I’d dreamed of some day going to the places where my hero Robert Falcon Scott had set off for his two Antarctic expeditions, especially the Terra Nova expedition of 1910-12 on which he raced Roald Amundsen to reach the South Pole first.1 Now, here I was, 63 years old, on a ship whose itinerary included—weather and ice permitting—a landing at Cape Evans: where Scott’s Terra Nova hut still stands.

I thought I would be mostly terrified—of the open water, of the cold, of the size of the ship (which was not, as these things go, very big at all). Instead, much to my surprise, I was exhilarated. Sailing in open water from Dunedin, NZ, with only seabirds in our wake, albatrosses swooping with their dynamic soaring, I found the view of nothing but sea to be exciting. The magnitude of all that water didn’t terrify. It awed me.

Days later, I found that getting into a zodiac (inflatable pontoon boat) wasn’t worrying at all, even if the little boat was tethered to the huge iron hull of the eight-deck-high ship. Matters of scale and proportion that have often freaked me out as a sculler on the Charles River were not an issue at all in the Southern Ocean or the Ross Sea. Still later, when given the chance to kayak in the Ross Sea, I took it, without batting an eye at the possible precariousness of a small craft in such cold water. And finally, days before our ship would be crossing out of the Antarctic Circle, I joined in with a couple dozen others for a polar plunge, jumping off one of the zodiacs and into 33-degree water.

If you had asked me months ago would I have done these things, I would have laughed in your face. I wasn’t even sure I’d be brave enough to get into a zodiac in all that ocean. And yet, I did. Each of these events and personal milestones came and went, offering only excitement and wonder, never fear.

I saved all my awe for one place: Scott’s hut.

It’s a cliche to say that I can’t describe the experience, or to say “I have no words”. Of course I have words. I never don’t have words. But still, there is something about the experience of walking into Scott’s hut that is utterly inexpressible. To cross that threshold is to step back to 1912, to feel that the men who sheltered there have merely stepped outside and will soon be back. Their presences aren’t even the presences of ghosts. It’s more than that. It’s as if they are and could be still there.

When I stepped inside, I couldn’t speak. I didn’t want to speak. And for several hours later, I couldn’t start to talk about it without choking up. In the hut itself, I was overwhelmed with emotion. This was where my hero lived and planned his expedition, the expedition that claimed his life weeks after he reached the Pole to find he’d been defeated. My trip to Antarctica was a pilgrimage to just this place—this place I had no guarantee of being able to visit—so I could pay my respects to the hero of my entire life. I still can’t believe I was fortunate enough to do it. Still can’t believe I didn’t let myself reserve this as a wish never fulfilled, can’t believe I was lucky to be able to make that transformation happen.

There is a word in Greek for what I felt inside Scott’s hut and even outside, surrounded by all that Polar ice: πελαγωσα. The English word pelagic comes from the Greek word pelagos, which means ocean. When you are overwhelmed, in Greek, you turn the noun for ocean into a verb. You have been oceaned. You needn’t be experiencing anything nautical to say it. Any kind of awe will do. In Scott’s hut, πελαγωσα. Πελαγωσα at the importance of the space, at what it meant that I stood in the same place where Scott had once stood.

I wonder now how it would have felt if we had not been able to go ashore at Cape Evans. When we reached nearby Cape Royds, for instance, where Shackleton’s hut still stands, the shore was encased in ice too thick to break through, and so the Shackletonians on board were left to gaze at that historic shelter from afar. I tried to imagine how they must have felt—how I would have felt if the opportunities had been reversed and we’d been prevented from visiting Scott’s hut and I’d stood instead inside of Shackleton’s. Here, I do in fact run out of words. Now that I’ve lived my dream (a phrase which is astonishing even to type), I can’t express the idea of its absence. I hope I never forget what it was like to step inside, ducking through the low door, and standing in Scott’s space.

As I said, I never don’t have words.

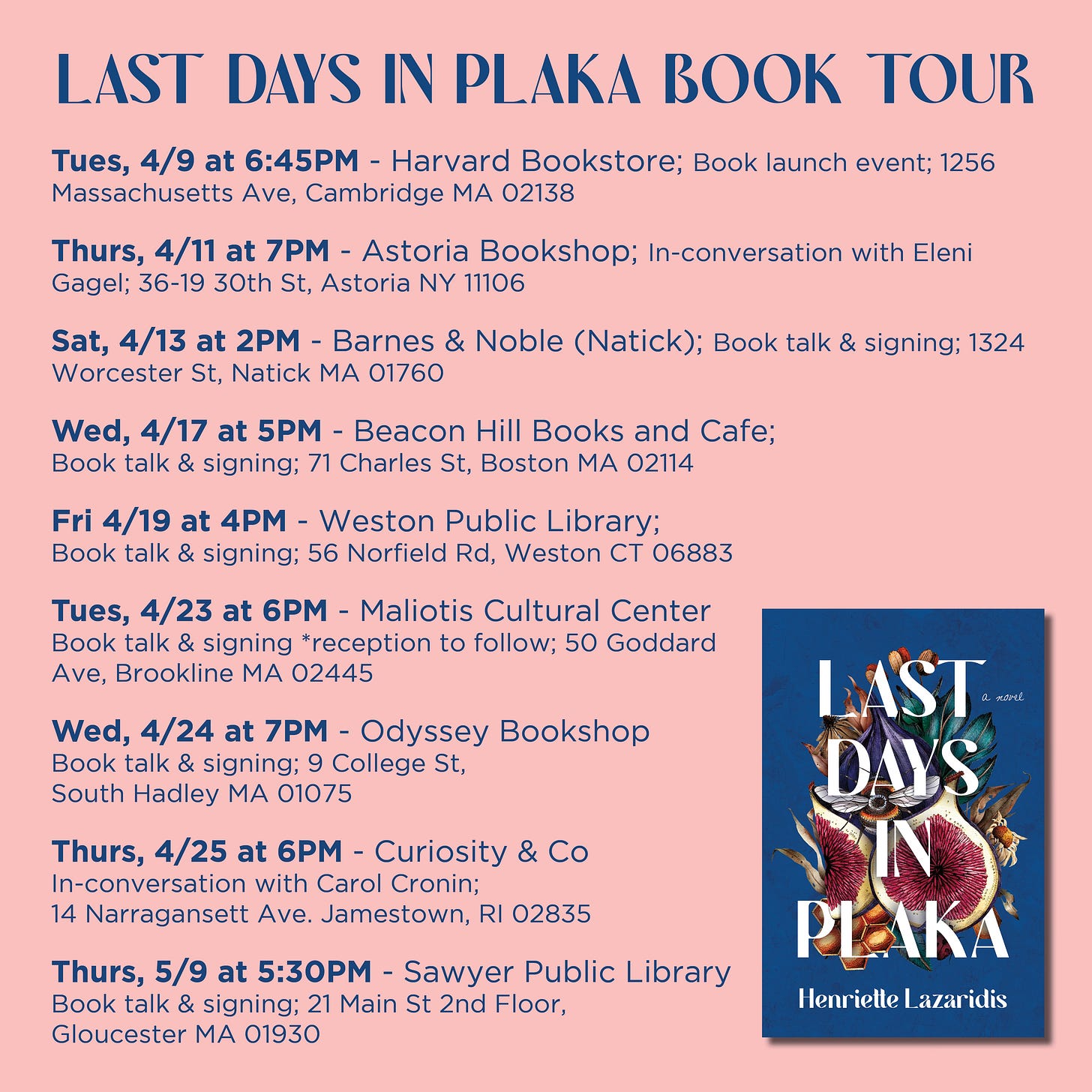

This April, I’ll have about 230 more pages of words out in the world, in the form of my third novel Last Days in Plaka. If you prefer to travel vicariously to climes warmer than Antarctica, this novel is for you! Set in contemporary Athens, it follows the unlikely friendship between an old Athenian woman and a young Greek American woman, each one searching to reconcile her life with what’s past and what’s to come. I’ll be doing a bunch of events, possibly in your area—or in the area of people you know. I’m also scheduling Zoom events with book groups and libraries. Nothing helps a novel find its audience more than word of mouth. And nothing sparks word of mouth more than people coming to events. Please come join me at one or all of these. While we’re at it, please consider pre-ordering your copy (because pre-orders really help, you guessed it, word of mouth). I hope to see you this April and May!

I'm so impressed by your intrepid travel. What a pilgrimage! Congratulations on your forthcoming novel too.

Good luck with the launch. Love the locale. At least not set in NYC, which has become almost a genre of its own : )