We had a very hot spell last month in the Boston area. High temperatures and extremely high humidity. The weather apps all signaled their warnings in dark orange and in all-cap text. High heat, they said. Don’t go outside.

I went outside.

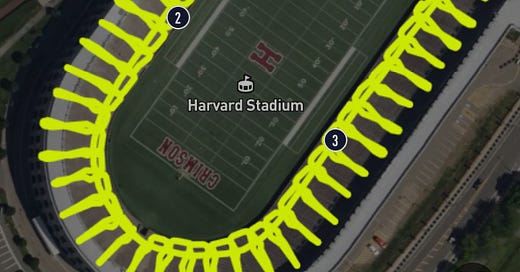

I was in the last few weeks of a training period that had begun in mid-April for a 33km mountain trail race set to take place July 21st. Working on a plan I had put together myself, I was building up to stacked workouts that combined one weekend day of, say, 4 hours of running, and the other weekend day spent gaining altitude in Harvard Stadium. By putting these workouts back to back, doing the stadium stairs on legs already fatigued by a long trail run the day before, I figured I could prepare for the stated 2,500 meters of elevation gain (that’s 8,200 feet) (that’s just under 2 hikes to the summit of Mt. Washington by the Tuckerman Ravine Trail). It was a good plan (more about that later*). Except for the heat.

Despite the weather warnings, I continued to train. Sure, I scheduled some of these workouts for the slightly cooler parts of the days (were there any slightly cooler parts?), and of course I took hydration and nutrition with me. But I made some tactical errors, and I was lucky they didn’t cost me heavily. Instead they taught me a lesson about humility and preparation that I feel applies to much more than sports.

Mistake #1: I hadn’t gotten around to restocking my supply of the energy foods I prefer to use for very long efforts.1 So I was grabbing what I could find before running out the door: a handful of nuts, maybe a Clif bar or two, depending on how long I’d be out there. I was decidedly not taking enough carbs or calories with me.

Mistake #2: Because I hadn’t restocked, I also didn’t have any electrolytes to add to my water bottles. I was amply hydrated while at my desk and at home before those workouts, but when you sweat as much as I do (also: see, hot weather and high humidity), you lose a huge amount of electrolytes. Water alone isn’t going to replace them.

These two mistakes share an origin: I didn’t take the heat warnings seriously because I assumed I would be fine. I assumed that, since I was well trained, in shape, strong, I would get through the workout without any unusual level of difficulty. And, because I had a plan, I felt I could stick to it. I had stuck to it remarkably well for months, and surely should continue despite the cautions I was reading and hearing and feeling all around me.

My rude awakening came one Wednesday at the stadium. I hadn’t even done one of the long runs the day before so I had relatively fresh legs (though my watch app had been telling me for days that I was in the “exhausted” range of [non]recovery). I began my workout of running up the steps (not the seats; I’m too short and/or have no bounding ability for that) for all 37 sections. But the heat was in the 90s and the humidity was in the 80% range. Very early into the workout, I began getting lightheaded. I kept stopping at the top and maybe sitting for a second or just holding onto the railing and letting my legs recover. I drank my water and ate my bars, but it didn’t really do much. I eventually finished the tour of the sections, ran the short distance home, and headed straight for the shower. Which was where I saw my face in the bathroom mirror.

My lips were blue. Deep blue. And my eyes were pretty sunken and my face was fairly pale. I had already gone through the stage of getting goosebumps in hot weather, which rings the first alarm bell of dehydration. I knew I was dehydrated. I hadn’t thought it could get that bad, or that it would really matter.

A simple google search will tell you my dehydration was severe. I could have fainted—which could have been disastrous in a stadium of concrete stairs and seats.

What I was ailing from most of all, though, was hubris—that ancient Greek concept of a self-confidence that brings the individual to see themselves as god-like. I somehow didn’t think the rules—of hydration and safe training—applied to me. Sure, sure, it’s dangerously hot out, I’ll go train, I’ll be fine. Not so.

It was a chastening experience. I felt almost ashamed about it—for having been so cavalier, for having been so unprepared. And that was the thing: in the midst of my serious preparation, I had overlooked certain essentials. Despite my serious preparation, I had in fact risked derailing everything. It took me days to really regain the ground I lost that day in the stadium. That Sunday, when I did my long trail run, my legs were still dead. No amount of electrolytes (which I began drinking with the zeal of the converted) could overcome the hole I had dug for myself earlier in the week.

Hubris and its god-like behavior. The zeal of the converted. There’s an ethico-moralistic streak to my words. Maybe that’s because I’m writing this newsletter in Greece, where hubris endures in the folklore of the evil eye that will curse you with bad luck if you express too much happiness or pay too high a compliment.2 But it could also have to do with the fact that, when we come face to blue-lipped face with a lesson, we tend to place it within our individual and personal moral framework. Or at least I do, as I try to learn from my mistakes. If I get zealous in my “conversion” to new wisdom, that’s a good outcome. I won’t be making the dehydration mistake again.

*Which brings me to the race I did on July 21. I’ve done this race at its different distances five times before, starting with the 10k, then the 21km, and then the 44km three times. This year, the distances have all changed—with the route adapting to the newly hotter summers in this region of northern Greece—and, along with my friend Sue who joined me last year, we did the new 33km distance. Per mile, this route had slightly more elevation gain than the 44km of previous years, including one lengthy ascent on a switchback of stone “steps” built centuries ago by the villagers as the only road between two settlements. We hit this stretch in blazing sun that reflected off the limestone all around us. And then we continued on upwards for another two or three miles before the final descent (down more stone “steps”) to the finish line.

It was a challenging race. But I had trained for steps, climbing all those stadium sections and even doing a double tour on my last big training weekend. And I had—finally—taken the hydration seriously. Seriously enough that Sue and I were drinking electrolytes for days ahead of time. As she did last year, Sue beat me again this year, catching me in the village of Vradeto at the top of that long stepped switchback and steadily moving ahead enough so that I couldn’t catch her on the downhill where I’m faster. She was a beast and came in third in the age group, bested by an Australian and a Greek who surely must have been babies in the 60+ category to our 64 and 63 (alas, there is no 70+ and so there will be no age-group gaming at the start of my 8th decade).

The result isn’t the only thing I take away from the race. In fact, quite uncharacteristically, I didn’t even check results beyond learning I was age-group 4th. My time did matter to me, but only as an expression of how I had beaten my own target and not as a competition or comparison with anybody else. Looking back at my two previous races where I’d bonked3, and the one where I’d done really well, I had set my goal somewhere between those two—and bested it. And the reason I bested it? I had learned from my training mistakes.

Lesson #1: hydrate with electrolytes. Water is not enough!

Lesson #2: Take care of yourself.

What do I mean by take care of yourself? I had been cavalier in thinking I would be unaffected by high heat and humidity. But at heart, the problem was that I wasn’t caring for myself sufficiently.

I was assuming that because something is difficult, I should accept any and all levels of difficulty associated with it.

That’s simply not true, nor is it helpful in life. Plenty of things are difficult. Writing books is difficult. Earning a living is difficult. (Earning a living while writing books is super difficult.) Caring for our loved ones is difficult. That doesn’t mean we should accept a struggle we can avoid. There is no added nobility in doing so. There are almost always ways to make a difficult task or experience easier. We need to look for them, and we need to use them.

Taking care of yourself means looking for ways to ease things, and also setting appropriate goals (which, when you get right down to it, is the key way to ease things). This is one of the things I love about trail running. You can’t set a pace goal, really. You can’t even hold a pace (not most of us, anyway). Because the terrain will snatch that goal from you and make you walk or scramble or speed downhill accordingly, wreaking havoc with any attempt you might make at consistency. Like life!

And so we prepare, we assess, we set a goal that depends not on competition and comparison, and we take ourselves seriously enough to not assume we are immune to weakness. That’s how we make our way—at whatever pace we choose—towards success.

For reference, when you’re doing a long effort of more than an hour or so, you need to replace carbs and calories, and you need to do it in a way that suits your stomach. As you go deeper into a running event of many hours, it gets harder to even want to eat. So the foods you carry will be foods you’ve trained with and can reasonably rely on.

This is why Greeks will, say, compliment a person’s baby and then say “ftou” as a faux-spitting sound, to fool the evil eye into thinking they find the baby so disgusting they are spitting at it.

I’m using this not in the British sense! but in the competition sense, where it means to utterly lose energy due to poor fueling.

Wow, Henriette! As with most of your athletic feats (and Sue’s!) this is both inspiring and daunting. There definitely was some kind of god, possibly a Greek one, looking out for you and saving you from passing out when you went running up those stairs and turning blue!

PS I somehow don’t get the message from your story that one should avoid pushing oneself to inhuman limits. I get the sense that with all your experience, you might have made it almost a practice to do just that. E.g. you got to where you are today and your extraordinary accomplishments by pushing yourself relentlessly, by pushing yourself “beyond.” That’s why you thought you’d be OK, pushing yourself even a little bit farther. There is joy in that, afterwards and you remind us of that. However I guess the current severe heat is a kind of limit, even for people like you with extraordinary abilities, and the ability to “fly” up or down a hill. it is interesting to revisit the electrolyte factor. You may inspire the super-cautious among us to try harder! But thanks for mixing in a little wise warning, with the inspiration.

There's a lot of wisdom in this post! Bravo on training seriously and learning from mistakes, and on racing with aspirational but achievable goals. I'll link to this in my Wednesday newsletter.