This past Sunday, I ran the Athens Marathon, more or less along the route that originated the very concept of the marathon run, from the town of—yes—Marathon (or Μαραθονας) to downtown Athens. If you are a runner or know a runner or know anything about the ancient Greeks and the Persians, you know the story that in 490 B.C.E., Pheidippides ran from the Battle of Marathon to Athens to announce the news that the Greeks had won. He apparently perished as soon as he delivered the message.

I did not perish upon finishing, and my message once I arrived at the finish line was a WhatsApp post to my cousin who had come in well ahead of me, asking “where are you?”. I did not perish, but I discovered that this marathon, this Athens Marathon the Authentic (as it’s branded), is one bear of a course, and that course, and the dehydration I was battling from Mile 10, really took me by surprise.

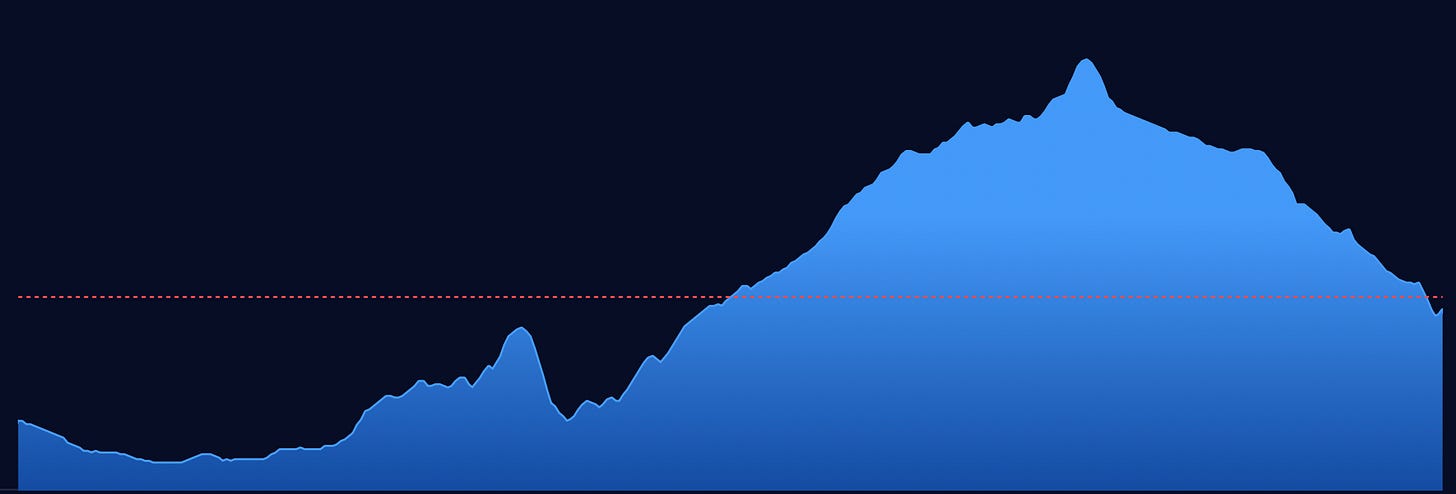

I’ve now completed four road marathons, and this course is by far the most challenging. While Boston has its starting downhill miles which tempt runners to go out too fast and then pay the price, and then has its three hills that culminate with Heartbreak Hill at Mile 20, the Athens Marathon has only one hill. One unbroken uphill that lasts—wait for it—for 8.75 miles. And when I say “unbroken” I truly mean that there is no flat section, no respite, from about Mile 11 to Mile 20. It’s killer.

My race last Sunday was an exercise in readjusting goals. I saw my optimistic time goal become impossible, and then I saw my conservative time goal become impossible, and then I told myself to just stay with it and finish, and to do my best to make up some time once I crested the abominable hill. And this, I did. Much of those last six miles took me down a boulevard that was the central route from my grandmother’s house, and then my mother’s house, into the center of Athens. I ran along shopfronts and neo-classical buildings and office blocks I’ve been driving past for my entire life. I’m proud of my effort. I ran those last six miles, through booming loudspeakers and bands and past witty signs and cheering, with a faster and faster pace for each mile. I crossed the finish line inside Kallimarmaro stadium at my fastest pace all day.

But this newsletter isn’t really about my race result or my athletic performance. It’s about what it’s like for me to be here, now, in Athens, spending time with my family and friends, having participated in an experience that truly feels like it should be a rite of passage for any Greek. Yes, there were plenty of international runners among the 21,000 registrants (of whom only 17,000 ran and completed the race). But the Athens Marathon feels very essentially Greek. Why?

The chatter among runners along the way, laughingly cataloging aches and pains or asking after friends elsewhere in the pack,

The particular Hellenic rhythm of the cheers from spectators, which I can best render as PAH—PAH—pah-pah-PAH,1

The way that the volunteers at the aid stations called out that they had νερακι. Not “water”, but “little water”—which is the affectionate diminutive that a Greek person almost always uses for this life-giving substance, so crucial in a country so hot and, often, dry,

The woman handing out olive-stem crowns at the 5km mark, which many runners wore for the duration of the race, the olive leaves bobbing and bouncing from their hair or their hats.

And nothing makes you feel you belong in a city more—I think—than walking through the downtown wrapped in a space blanket with a race medal around your neck. Athens was mine on Sunday. Or rather I belonged to the city.

Someone I knew well once heard me say something in a conversation and then paused, scrutinized me, and said in wonderment:

“You’re not really from here.”

And by “here”, he meant the United States. He was right. The realization hit us both that instant as somehow getting to the truth of my experience for the first time. I was born in the States, but apparently you can’t tell that when I speak Greek (or so I am told). My parents never thought of themselves as immigrants (which technically they were, having gone to the States when they were in their early 30s). They behaved more like expats. They were always planning to return to Greece, the country in which we spent three summer months each year, and to which they returned for six months yearly once my father had retired. Soon after my father died, my mother turned the half-year into full. My parents’ sojourn in the States was like a wave that washed up on shore long enough to deposit me, and then retreated.

Even though I have never lived in Greece—except for those three-month summers—every time I arrive at the airport, I feel a sense of ease and relief. Not that being in the United States is in itself a stressful thing. But arriving in Greece feels to me like the end of a displacement. The scents of the air—jasmine, eucalyptus, Seville orange blossoms if it’s winter time, the petrichor after rain, even the unique scent of car exhaust here, or cigarette smoke—are all weirdly comforting to me. Even if I don’t like the smells (see: exhaust, cigarette smoke), I love experiencing them. Those scents tell me I am home.

Greeks come by displacement honestly. Many have emigrated, in waves, including to major diaspora centers like Chicago, New York’s Astoria, Melbourne, or Tampa, or Worcester, Massachusetts. In addition to that almost-one-way emigration, there is something Greeks call ξενιτια or xenitia (emphasis on the last syllable)2. As with words like saudade in Portuguese or maybe sisu in Finnish, it’s very difficult to translate xenitia. But perhaps the best explanation would be that it’s a voluntary exile, complete with the associated nostalgia3 for the place you’ve chosen to leave behind. In my family specifically, we are experts in xenitia. My maternal grandfather went abroad to Switzerland for his business degree. His eventual wife came abroad from Switzerland to Greece and stayed. My paternal great-grandfather traveled to a business in Romania, essentially commuting from northern Greece to Turnu Severin on the Danube and as far east as Odessa. My parents left what sounds like a good life in post (two)-war(s) Athens for what they felt would be an adventure in Boston. Home, in my family, is always somewhere else.

I suppose I’m carrying on a tradition of xenitia in the way that I feel about Greece, this county I was not born in but somehow born to. I miss Greece when I’m in the States. But then again, being displaced from Greece is a condition I’m so accustomed to that missing Greece doesn’t always take conscious, active form. Still, it’s always there, and it pops up in ways that surprise me. When I’m not in Greece, if I overhear Greeks talking, I’m so delighted to hear this language I love to speak that I have to stop myself from joining their conversation. Or if I happen to be looking at a map of Greece, or reading about Greece in the paper or some online article, I will mutter to myself in Greek without realizing it. The wiring fires and wakes up the connection that’s always there, always ready.

For me, this is a lovely and a lonesome thing, the way I live apart from the language (and so many of the people) that I love, apart from the language in which I feel a deep connection to myself. It’s not that I’m more myself when speaking Greek. It’s as if I have two selves at once, English and Greek each expressing a different Henriette4. To be in Greece and to speak Greek every waking minute reunites me with an essential part of myself that otherwise goes missing.

I know I’m not alone in this sense of displacement. I’m guessing that any number of you all reading this will report similar experiences with the countries and cultures that you and/or your parents were raised in. I’d love to hear your experiences of this thing I can’t quite name—and not for lack of trying, or language.

Today, the day after the marathon, I was in downtown Athens and I encountered a man wearing a suit jacket and tidy trousers and a white business shirt—and his medal from Sunday’s race. I smiled and said “Μπραβο! Συγχαρητηρια!”5 And he said thank you. And then, as I moved away, because Athens is mine now in a way that it wasn’t before, I called back to him, “Me too!” But really I said, “Και εγω!”

This is the rhythm, not the actual words, of course!

This laptop’s interface doesn’t do Greek diacritical marks for stress.

Not to get all Gus Portokalos on you, but nostalgia is a Greek word. It’s the sickness (algia) for home (nostos).

For those playing at home, it’s true that Henriette is not a Greek name. Xenitia left its mark on me and I am named for my Swiss grandmother.

“Bravo! Congratulations!”

Yes, all of this! When I return to Paris, it's the sounds that are the most comforting, the most I-am-home-y although I haven't lived there since 1991. The voice and cadence of the announcer at the Charles de Gaulle airport. The tap-tap of heels echoing in quiet streets on Sunday mornings. The click and groan of heavy, green doors leading to courtyards. The creak and clack of shutters being pushed open. And I've been told my voice is different in French. I do feel like a different Anjali in French.

I really loved this post. I cannot relate to being an expat yearning for my true home country, but I can relate to running a marathon through a place where each mile evokes memories and a feeling of belonging mixed with nostalgia, triggered by scents as well as sights. Congratulations on your strong finish.