The Hardest Thing I've Ever Done

Or, how I finally started ski touring the way my parents used to do

One day last March, I found myself in my car, freezing cold, with the heat turned up high, groaning. I had just finished my first ever skimo race, which took me 3 1/2 hours and involved skiing up Mount Greylock and then coming down the Thunderbolt trail. Twice. As I sat in my car and tried to get warm, removing what sweaty clothing I could and throwing on multiple dry layers, still gasping for air, I realized it was the hardest physical thing I’d ever done. I said that then and I stand by it:

Completing the recreational level of the Thunderbolt Ski Race remains the hardest physical thing I’ve ever done.

I can’t wait to do it again this year.

Skimo, you say? What is that? As of this coming Winter Olympics, it’s an Olympic sport, but it’s had a long heritage at the international level already. [By coincidence, today’s New York Times contains an article about ski touring and its exponential, pandemic-times, growth.] I’m a fangirl, I guess. I follow skimo racers on Instagram and I watch and rewatch the videos of the moments when they switch their skis from uphill mode to downhill mode (more about this later). I’ve joined Facebook groups like New England Rando that puts together a race series I someday want to do. Mostly I marvel at the fitness of these athletes. That day on Mount Greylock, I was plugging along uphill at a steady pace, surely at my anaerobic threshold, and these spandex-clad individuals from some other species practically ran up past me, always saying a sincere (really. I could tell) “good job” as they sped by. Perhaps they knew that, though slow, I was indeed working my hardest—and deserved some praise—because they could see I was using equipment designed not for racing but just for touring up and down mountains. Their race skis were super skinny and had bindings smaller than a C battery, designed to spin from one mode to the next while the skier is still in them. My skis were wider and my bindings took me considerably more time to switch modes. I had practiced transitions on my living room rug, learning how to use my ski pole to rotate the heel piece 90 degrees so I could step into it as you do on a downhill binding. Let’s just say it took me much longer on race day, in the cold, when I was sucking wind each time I reached the top of Greylock.

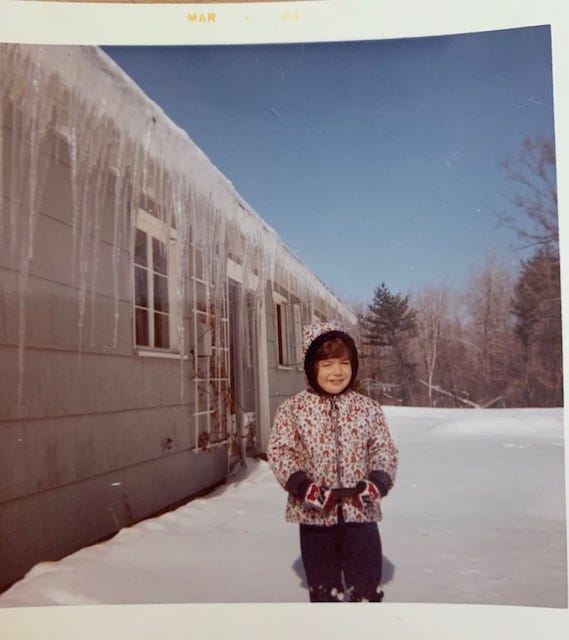

The skimo race was a kind of culmination of a lifelong dream of mine. A skier from the age of three, I’d long wanted to do the kind of skiing my parents had done in their native Greece: sliding up a mountainside on skis equipped with animal skins—to use the reverse nap of the fur for grip—and skiing down untracked powder. Yes, there is wonderful skiing in Greece, and before they even met, my parents went on numerous outings to some of the same mountains—Ziria, Parnitha, Parnassos—skiing entirely under their own power. Old photos show them surrounded by powder snow, above treeline, making great swooping turns on long wooden skis or standing in rows for the camera with their friends, outfitted in hand knitted sweaters and wool knickers. My mother famously had to share a pair of boots with a cousin, and you can see her in a photo or two with changing footwear during the day’s adventure as the boots went back and forth. My father preserved his ski-touring way of skiing down even on the modern skis of the 1990s, swinging his upper body to the left and right as if he were still hauling heavy long boards around the arc of a turn.

When my parents took me out on the slopes as a little girl in New England, I know they enjoyed the ease of a chairlift or a t-bar. But they agreed that there had been glamor in their Greek skiing that was missing now. Their kind of skiing was so connected to the reality of a mountain. Fresh tracks, powder, silence, vistas. My kind of skiing involved ice, noise, narrow trails. I still loved to ski, but I also loved the lore of skiing, the atmosphere I imagined around the sport. That imagined scene was, after all, far more pleasant than desperately trying to hold an edge on Cannon Mountain’s notorious blue ice.

In my forties, I became bored with skiing, especially as skiing in New England took on what felt to me like a sort of amusement park atmosphere, complete with piped music and traffic on the trails. I had also begun to lose sight of potential new challenges in the sport. This is not to say I was a perfect skier, whatever that means. But I was good, and I could do mostly what I wanted on most any trail. That, coupled with the fact that my family skied the same resort all the time then, and usually the same two or three runs, made me indifferent to the sport. One winter went by and I didn’t ski a single day. A few years later, it happened again. I decided I couldn’t let that happen a third time. I couldn’t lose the sport in which I feel most natural. I sometimes say I ski better than I walk, so it was vital that I reclaim skiing for myself.

Early last January, I was riding a chairlift with my son at a tiny Vermont mountain and watched someone going up the skin track. I declared I wasn’t going to let another year go by without doing this thing I’d always dreamed of. It took me a couple of weeks to round up some second-hand equipment, and for my first outing, my shakedown cruise, I spent a few hours on Section 16 of Vermont’s Catamount Trail. My equipment was overkill for the rolling terrain of the out-and-back I did that day. But I didn’t care. I was finally doing it: pushing my skis uphill on skins, peeling the skins off and switching my bindings from free heel to locked heel, and then skiing down. A few days later, I went back to that little Vermont mountain on one of the two days each week when it is closed, and I skinned up the same skin track I had watched the other skier on at the beginning of the month. This was the real deal, going legitimately up the hill, gliding stride by gliding stride, so I could ski down. Last season, I skied that same mountain several more times, and I ventured to Mt. Watatic, an abandoned ski area in Massachusetts, the trails up Mt. Cardigan, the trails behind Stowe, glades in Brandon, and, of course, the Thunderbolt, which I skied for the first time two months before the skimo race, on a bluebird day of single-digit temperatures with six or more inches of fresh powder.

This is skiing.

You’re outside. There are few (if any) other people around. You stop when you want and pull your sandwich out of your backpack and throw your heavy down jacket on to keep warm. If it’s not frigid out, maybe you make a chair with your skis jammed into the snow. You’re often skiing trails that were cut in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, trails that are themselves legends in the sport. The Thunderbolt. The Bruce. The Burt. The Alexandria. You carry a pack carefully supplied with safety equipment. You are prepared, if need arise, to spend one night outside alone in the cold. If you’re me, you ski places with no avalanche risk, and if you have your AIARE training, you might venture. No matter what, you earn your turns, as they say, with steady hard work going up the mountain or the hill. And if you’re really lucky, you ski fresh powder, over boulders and logs, between the trees. You put the skins back on and you do it again. And again.

The Thunderbolt Ski Race was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But probably the most athletically meaningful thing I ever done had already happened a month earlier, the first time I took my touring skis to Mt. Ascutney.

Ascutney doesn’t operate a chairlift anymore, though it’s thriving as a community mountain with a rope tow and a t-bar. But many years ago, it was the little area in southern Vermont where my parents taught me to ski. 57 ski seasons later, in February of 2021, I was heading up the skin track, doing the sport that is perhaps more than anything my parents’ legacy, and I was finally doing it their way.

What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever done?

The hardest thing I have ever done is Ride the Rockies in 1993, my first of many week long bike tours. It was seven days of biking (no day off, as is customary), with many mountain passes, and a century day from Steamboat to Vail.

Sounds wonderful!! Nothing like being out in the snow with your heart pumping.